Specifying for Sustainability: An Earth Day Call to Action

Last week, during a CEU presentation, a rep highlighted the great qualities of two wood species, Ipe and Cumaru. Both are currently listed among endangered species. Seeing them presented as viable options left me deeply concerned.

The Amazon rainforest is home to an incredibly diverse range of tree species, many of which are now considered endangered due to deforestation, climate change, illegal logging, and land conversion for agriculture or mining. While these are complex global issues, nearly everyone agrees: preserving the Amazon is vital to the health of the planet.

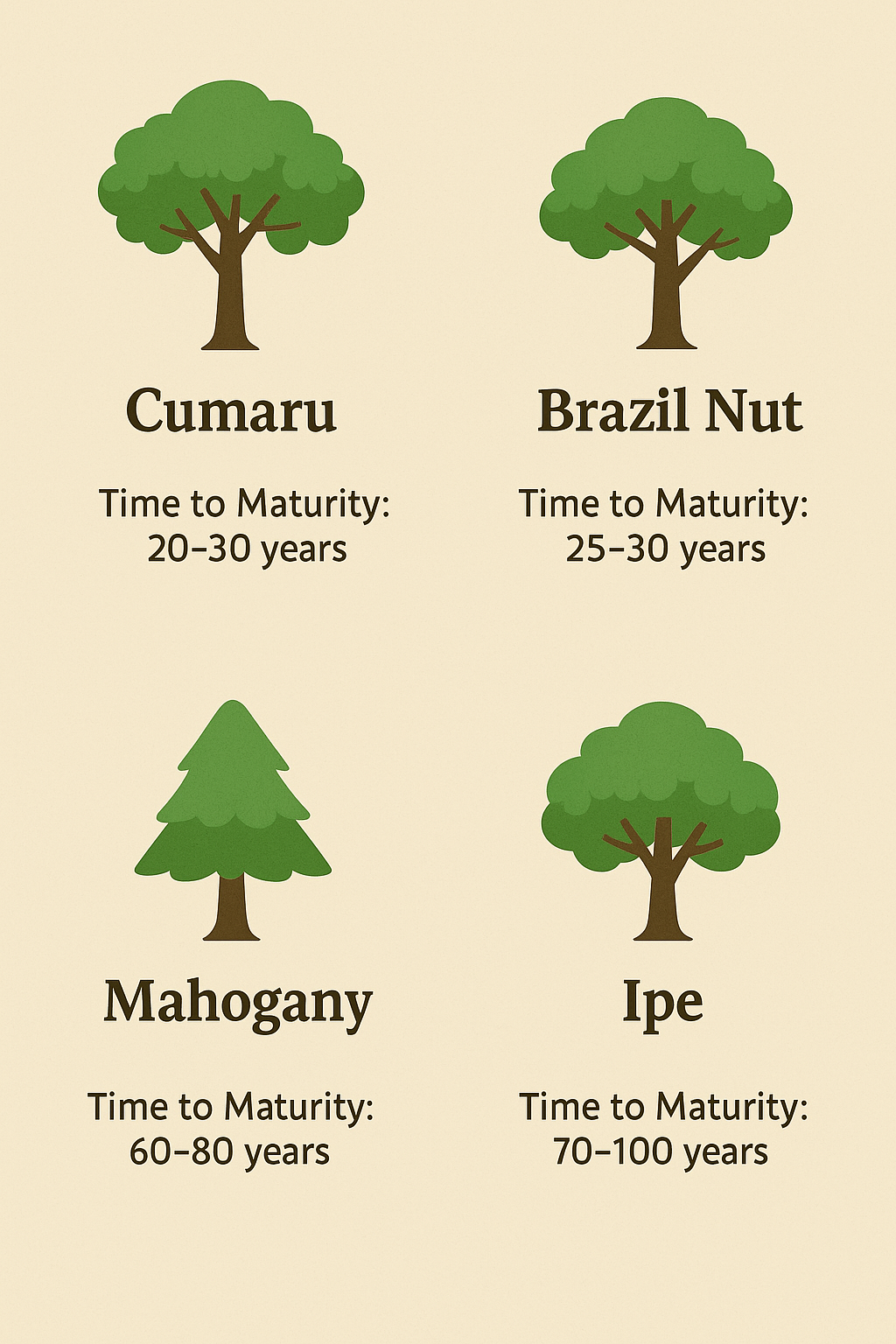

It’s astonishing that in the same era when humanity is preparing for missions to Mars, there are still uncontacted tribes in the Amazon—a powerful reminder of why this forest must be protected. As designers, we have a unique role in influencing the materials used in our built environment. We can help eliminate illegal logging by simply refusing to specify endangered wood species. It’s a small step, but over time, it can make a real impact—especially when you consider that a single Ipe tree takes 70–100 years to mature.

Recent reports indicate that the Amazon rainforest is home to nearly a third of the world's biodiversity, with new species of plants and animals still being discovered regularly. However, the rapid loss of this habitat might result in species disappearing before scientists have a chance to study them fully. From 2001 to 2020, the region experienced a decline of more than 54.2 million hectares of forest—roughly 9% of its total area, an extent comparable to the area of France. The Brazilian portion of the Amazon, which comprises 62% of the forest, has been the hardest hit, with significant losses also recorded in areas of Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia (Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature -IUCN).

Illegal timber enters the global supply chain through a series of interconnected processes. It begins with forest exploitation, where logging occurs in protected Indigenous lands, conservation areas, or public forests without proper permits, targeting high-value hardwoods like Ipe, Cumaru, Jatobá, and Mahogany. Fraudulent documentation further facilitates this illegal trade, falsely reporting wood as being harvested from legal zones when, in reality, it is extracted from unauthorized areas. The timber is then moved under legal paperwork through various checkpoints in the transportation and laundering phase, and once processed in sawmills or ports, illegal wood becomes indistinguishable from legally sourced stock. Finally, the timber is exported and sold in markets such as Europe, the U.S., and China, often bearing FSC-like certification or misleading "sustainable" labels that disguise its illicit origins.

How Designers Can Ensure FSC Wood Is Truly Responsible

Ask for Proof

Request FSC Chain of Custody (CoC) certificates and sales invoices.

Look for FSC 100% or FSC Mix Credit (not just “FSC Certified”).

Verify the Source

Use info.fsc.org to check certificate validity and scope.

Specify Clearly

In specs, require FSC-labeled wood with documentation.

Avoid vague terms like “sustainable wood.”

Use Trusted Suppliers

Work only with vendors that are FSC-certified and have traceable supply chains.

Consider Domestic Alternatives

Use U.S.-grown or lower-risk woods when possible to reduce pressure on tropical forests.

Be an Advocate

Educate your team and clients. Push for firm-wide responsible wood sourcing policies.

Deforestation and biodiversity loss are not abstract issues; they are actively undermining Amazonian ecosystems. As one of the planet’s most significant natural climate regulators, the Amazon plays a pivotal role in absorbing CO₂ and maintaining climate balance. Logging not only releases greenhouse gases but also erodes the forest’s resilience. Indigenous communities bear the brunt of these impacts—with many facing displacement or threats as they defend their ancestral lands.

And yes—buyers in the U.S. and Europe (including us as designers) may unknowingly support this chain. But the good news is: we can help disrupt it.